Žilionė R. (2023). Reinventing the STEM VET via Peer assisted learning and Innovative pedagogy. Global Academic Society Journal: Social Science Insight, Vol. 9, No. 19, pp. 13-19. ISSN 2029-0365 [www.ScholarArticles.net]

REINVENTING THE STEM VET VIA PEER ASSISTED LEARNING AND INNOVATIVE PEDAGOGY

Rasa Žilionė

Innovation Office, Lithuania

Abstract: The science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) vocational education and training (VET) sector faces many challenges in the 21st century, such as the rapid changes in technology, the increasing demand for skilled workers, the diversity of learners and the environmental and social issues. To address these challenges, this article proposes a novel approach to STEM VET that combines peer assisted learning (PAL) and innovative pedagogy (IP). PAL as a form of collaborative learning involves students helping each other to achieve learning outcomes, while IP refers to the use of new and effective methods of teaching and learning. The article discusses the benefits and challenges of PAL and innovative pedagogy for STEM VET, and provides some examples of how they can be implemented in practice. The article also suggests some recommendations and directions for future research and development in this area.

Keywords: STEM VET, peer assisted learning (PAL), innovative pedagogy (IP), collaborative learning, 21st century skills

Introduction

The STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) disciplines are crucial for the development of a skilled and innovative workforce that can meet the challenges of the 21st century. However, many students face difficulties in engaging with STEM subjects, especially in the vocational education and training (VET) sector, where the dropout rates are high and the outcomes are often poor. To address this issue, we propose a novel approach that combines peer assisted learning (PAL) and innovative pedagogy (IP) to enhance the quality and effectiveness of STEM VET. PAL is a student-centred method that involves collaborative learning among peers of different abilities and backgrounds, while IP is a pedagogical strategy that fosters creativity, inquiry, problem-solving and critical thinking skills. By integrating PAL and IP, we aim to highlight a supportive and stimulating learning environment that can motivate and empower STEM VET students to achieve their full potential. The paper presents the theoretical insights about integration of PAL and IP in the area of the STEM VET.

STEM VET is a key component of the education system that prepares students for careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields. STEM VET plays an important role in fostering innovation, economic growth and social development, as well as addressing global challenges such as climate change, health and security (OECD, 2019).

However, STEM VET also faces many challenges in the 21st century, such as:

– The rapid changes in technology and the labour market that require constant updating of skills and knowledge (World Economic Forum, 2018).

– The increasing demand for skilled workers in STEM fields that exceeds the supply of qualified graduates (OECD, 2019).

– The diversity of learners in terms of their backgrounds, abilities, interests and motivations (European Commission, 2017).

– The environmental and social issues that require STEM VET to promote sustainability, equity and inclusion (UNESCO, 2017).

In this article, we will review the literature on PAL and IP in STEM VET contexts, discuss the benefits and drawbacks of this approach, and provide some recommendations for future research and practice.

Peer assisted learning (PAL)

PAL is a form of collaborative learning that involves students helping each other to achieve learning outcomes (Topping & Ehly, 2001). PAL can take various forms, such as peer tutoring, peer mentoring, peer feedback or peer assessment. PAL can be implemented in different settings, such as face-to-face or online, formal or informal, structured or unstructured. PAL can also involve different types of peers, such as same-age or cross-age, same-level or cross-level, same-discipline or cross-discipline. PAL has many benefits for STEM VET students, such as:

– Enhancing academic achievement by providing additional support and practice opportunities (Topping & Ehly, 2001; Guraya & Abdalla, 2020; Zhang & Maconochie, 2022).

– Developing metacognitive skills by encouraging reflection and self-regulation (Hattie et al., 2017).

– Improving motivation and engagement by creating a sense of belonging and community (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

– Increasing confidence and self-efficacy by providing positive feedback and recognition (Tullis & Goldstone, 2020).

– Promoting social skills and intercultural competence by facilitating interaction and cooperation among diverse peers (Johnson & Johnson, 2009).

PAL involves students from similar social groups who help each other to learn and learn themselves by teaching (Topping, 1996). PAL activities allow students to practice and develop their healthcare and teaching skills in a collaborative and supportive environment (Burgess et al., 2020). However, PAL also poses some challenges for STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) VET (vocational education and training) students, such as the quality of tutor training, the availability of resources, the motivation of participants, and the evaluation of outcomes (Secomb, 2008).

Peer-assisted learning (PAL) is an educational method that involves students from similar social groups helping each other to learn and learning themselves by teaching (Topping, 2001). PAL has been widely used and accepted in various health professional education settings, such as clinical schools, where students can practice and develop their healthcare and teaching skills (Burgess et al., 2020). However, the effectiveness of PAL in a vocational education setting has not been extensively studied. This article aims to review the existing literature on PAL in vocational education and to provide some practical tips for planning, implementing and evaluating PAL activities in this context.

PAL in vocational education can offer several benefits for both tutors and tutees, such as enhancing motivation, confidence, communication, collaboration, feedback and skill acquisition (Leijten & Chan, 2010). However, PAL also poses some challenges, such as ensuring the quality of peer teaching, managing conflicts, addressing individual differences and providing adequate training and support for peer tutors (Boud & Lee, 2005). Therefore, it is important to design PAL activities that are aligned with the learning objectives, curriculum and assessment of the vocational courses, and that are based on sound pedagogical principles and evidence.

Some of the key steps for planning PAL activities in vocational education are: identifying the learning outcomes and content to be covered by PAL; selecting appropriate peer tutors and tutees; designing effective peer teaching strategies and materials; providing tutor training and ongoing feedback; and monitoring and evaluating the PAL process and outcomes (Burgess et al., 2020). Additionally, some of the factors that can influence the success of PAL activities are: the agency of the students, that is, their willingness to participate and take responsibility for their own learning; and the affordance of the activity and the workplace, that is, the invitational quality and support provided by the vocational school and the instructors (Raupach et al., 2022).

In conclusion, PAL is a valuable educational method that can enhance the learning experience and outcomes of students in vocational education. However, PAL requires careful planning, implementation and evaluation to ensure its effectiveness and quality. Further research is needed to explore the impact of PAL on different vocational disciplines, settings and student groups.

Practical implementation

PAL and IP methodology in the field of STEM VET is applied in Erasmus+ project “Reinventing the STEM VET via Peer assisted learning and Innovative pedagogy” (iPeer) with the aim to enhance the quality and relevance of vocational education and training (VET) in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). The project uses peer assisted learning (PAL) and innovative pedagogy (IP) as the main methods to foster the development of key competences and transversal skills among VET learners and teachers. PAL as a collaborative learning approach involves students helping each other to learn and improve their academic performance, while IP is a creative and student-centred teaching approach that uses various tools and techniques to enhance learning outcomes and motivation. The project involves 8 partners from Bulgaria, Lithuania, Kazakhstan, Portugal, Germany, Slovenia and Spain, who designed, implemented and evaluated a comprehensive STEM VET curriculum, a PAL and IP toolkit, an online platform and created a network of STEM VET ambassadors. The project expects to reach more than 2000 VET learners and teachers, as well as other stakeholders in the STEM VET sector, and to contribute to the improvement of the quality, attractiveness and innovation of VET in Europe (iPeer, 2023).

STEM VET (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Vocational Education and Training) is a key area of education that prepares learners for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century. STEM VET can foster creativity, problem-solving, collaboration and innovation skills that are essential for the future workforce. However, STEM VET also faces some challenges, such as low enrolment and retention rates, lack of diversity and inclusion, and gaps in quality and relevance.

One possible way to address these challenges is to adopt peer assisted learning (PAL) and innovative pedagogy (IP) in STEM VET. PAL is a form of cooperative learning that involves students helping each other to learn through structured activities, feedback and reflection. IP is a broad term that encompasses various teaching and learning approaches that aim to enhance student engagement, motivation, autonomy and achievement. Examples of IP include project-based learning, inquiry-based learning, gamification, flipped classroom and blended learning.

PAL and IP can offer several benefits for STEM VET, such as:

– Improving academic performance and retention rates by providing students with more opportunities to practice, review and apply their knowledge and skills in authentic contexts.

– Enhancing social and emotional skills by fostering positive peer relationships, communication, teamwork and leadership.

– Increasing diversity and inclusion by creating a supportive and respectful learning environment that values different perspectives, backgrounds and abilities.

– Promoting lifelong learning by encouraging students to take ownership of their learning process, set goals, monitor progress and reflect on outcomes.

Practical implementation of PAL and IP in the field of STEM VET is successful in many cases, however, requires careful planning, coordination and evaluation to ensure its success in different contexts.

Recommendations and conclusions

This paper recommends that STEM VET educators and stakeholders consider implementing PAL and IP in their courses and programs. To do so, they need to:

– Conduct a needs analysis to identify the specific learning objectives, outcomes and challenges of their STEM VET context.

– Select appropriate PAL and IP strategies that align with the needs analysis and the curriculum standards.

– Design and plan the PAL and IP activities with clear instructions, roles, expectations and assessment criteria.

– Implement the PAL and IP activities with adequate support, guidance and feedback from teachers and peers.

– Evaluate the PAL and IP activities with valid and reliable methods to measure their impact on student learning and satisfaction.

– Check existing educational resources such as Erasmus+ project „iPeer“ (ipeer.org) or other resources.

By following these steps, STEM VET educators and stakeholders can enhance the quality and relevance of their education provision, as well as the skills and competencies of their learners.

Although a number of scientific papers is prepared in PAL, IP or STEM VET fields. However, scientific researches in complex of the mentioned fields are not so often found. Therefore, more scientific attention could be paid to these fields as a complex, its application in practice and impact on VET teachers and students.

References

1. Boud D., Lee A. (2005) Peer learning as pedagogic discourse for research education. Stud High Educ. 2005;30(5):501–16.

2. Burgess A., van Diggele C., Roberts C., Mellis C. (2020) Planning peer assisted learning (PAL) activities in clinical schools. BMC Med Educ, 20 (Suppl 2):453.

3. European Commission (2017) Diversity and Inclusion strategy of the European Commission.

4. Guraya S. Y., M. E. Abdalla (2020) Determining the effectiveness of peer-assisted learning in medical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2020 Jun; 15(3): 177–184.

5. Hattie J., Fisher D., Frey N., Gojak L. M., Moore S. D., Mellman W., Briars D. J. (2017). Visible Learning for Mathematics, Grades K-12: What Works Best to Optimize Student Learning. Published by Corwin, SAGE Company.

6. iPeer (2023) Erasmus+ “Reinventing the STEM VET via Peer assisted learning and Innovative pedagogy” (iPeer) website. Available at: www.ipeer.org

7. Johnson D. W., Johnson R. T. (2009). An Educational Psychology Success Story: Social Interdependence Theory and Cooperative Learning. Educational Researcher, 38(5), 365–379.

8. Leijten F, Chan S. The effectiveness of peer learning in a vocational education setting. Ako Aotearoa Southern Hub; 2010.

9. OECD (2019), Education at a Glance and UNESCO Institute for Statistics Database (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, n.d)

10. Raupach T, Grefe C, Brown J et al. Does peer teaching improve academic results and student satisfaction? A randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2022; 22:35.

11. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78.

12. Secomb J. (2008) A systematic review of peer teaching and learning in clinical education. J Clin Nurs, 17(6): 703–16.

13. Topping K. J. (1996) The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: A typology and review of the literature. Higher Education, 32(3):321–45.

14. Topping K. J. (2001) Peer assisted learning: a practical guide for teachers. Newton: Brookline Books.

15. Topping, K. J., Ehly, S. W. (2001). Peer assisted learning: A framework for consultation. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation, 12(2), 113–132.

16. Tullis J. G., Goldstone R. L. (2020) Why does peer instruction benefit student learning? Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 5:15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-020-00218-5

17. UNESCO (2017). Cracking the code: Girls’ and women’s education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Paris.

18. World Economic Forum (2018). The way we teach STEM is out of date. Here’s how we can update it. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/12/hacking-the-stem-syllabus/

19. Zhang Y., Maconochie M. A. (2022) Meta-analysis of peer-assisted learning on examination performance in clinical knowledge and skills education. BMC Med Educ 22, 147.

Gudaitytė V. (2023). Social media and McLuhan in today’s education system. Global Academic Society Journal: Social Science Insight, Vol. 9, No. 19, pp. 4-12. ISSN 2029-0365 [www.ScholarArticles.net]

SOCIAL MEDIA AND MCLUHAN IN TODAY’S EDUCATION SYSTEM

Vaiva Gudaitytė

Vilnius University, Lithuania

Introduction

It would be harder to find anyone now arguing that technology is changing our daily lives and our understanding of life than it was in the 1960s when the Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan began to talk about media and its influence. “The message is the media” (McLuhan, 1964), he says, and pushes not the content, but what or whom the content affects to the top of the hierarchy of message influence. This scientist’s ideas, developed before the internet and computers reached our homes, sound like prophecies of the future we live in now. McLuhan introduced new concepts such as ‘Hot and Cool Media’ (McLuhan, 1964), the ‘Global Village’ (McLuhan, 2000), the ‘Tetrad model’ and the understanding of media as ‘Extensions of man’ (McLuhan, 1964), all of which are linked to contemporary life and the interactions with other people or media that take place in it. McLuhan argues that changes in technology and media are shaping and changing our societies and the way they function. Levinson (2001) argues that McLuhan’s ideas can help us understand our new digital age. This can also be seen in the current education system: McLuhan argues that the classroom we have and see now is a by-product of the press (also a media) (McLuhan, 1966). However, in today’s world, the popularity of the press is being taken over by computers, the internet, digitised materials, social media – things that McLuhan, in his texts, seemed to “foreshadow” when he spoke of the ‘Global Village’ and ‘Extensions of man’. Seeing social media as a message and a new technological transformation happening, according to the example with the press, should also deform the educational system. Social media has become an everyday reality that changes many areas of life and the perception of self, and it is no longer possible to overlook or not accept (as is often the case in schools) social media in the structures of learning, because it has such a strong influence on the everyday life of pupils, and it automatically deforms the structures of interactions and thinking. This essay will try to embody McLuhan’s ideas and not try to explain, but to observe how social media works in schools today and its possible impact on the future and the interpersonal relationships between teachers and students.

Keywords: social media, McLuhan, education system.

Social Media – “The medium is the message”

One of the key concepts and ideas explored by McLuhan – “The medium is the message”, is an important basis for evaluating social media in education. Understanding that the medium itself is a message and carries distinctive information is essential for choosing the right educational medium and for understanding what messages a particular medium can independently convey or how it can shape our perception of life (McLuhan, 1964). As McLuhan argues, the content of each medium is itself a medium/media. These characteristics are very easy to observe in social media. In this case, social media is becoming a new “technology” that is changing the interactions between human beings. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (2013), social media is defined as websites and applications/apps that allow users to create and share content or participate in social networks. This only confirms McLuhan’s ideas about the ‘Global Village’ and the understanding of content as media. A closer look at the concept through McLuhan’s eyes suggests that social media, although it emerged well after the author’s death, fits with the idea of a game-changing technology (media) because of the impact it has already had and is still having on changing everyday life, the ability to change the pace of communication and the transmission of information (things are speeding up), and the habits of mind. We expect to receive information much more quickly, the emotions of live communication are synthesised in ‘emojis’, the creation of a sense of proximity at a distance, the promotion of anonymity and individuality through a presumed sense of community, which manifests itself in the possibility of secretly ‘meddling’ in the affairs of others. This is not the direct content of the media, but the performance of the media itself and the possibilities it offers are already changing our perception of life and our expectations of ourselves and others (e.g., the desire to get things quickly – here and now). Returning to the question of content becoming media, in the case of social media, we also have to look back to the more traditionally understood technologies: the computer and the telephone. In these technologies (as well as in others), we can observe an emerging media fractal: the internet could be seen as the content of these technologies, but it is also a media in which there are social media, which is also a media and a content, in which other media and contents interact, in a way which in itself turns it into another media. This also shows the uniqueness of social media, which seems to be an infinite fractal that contains a constant mixing and interaction of hot and cool media: writing, language, sound, image, internet, browsers, different technologies, and a variety of other social media. These processes encourage the engagement of the assumed, synthesised senses and thus involve them in the simulations of life. Here we can already speak of questions of the reality of ‘reality’ and recall Baudrillard (1981), who argued that images of reality can overshadow reality itself. The space of communication is changing, which has its own obstacles and/or advantages for interpersonal communication and the transmission of the message, i.e., it forms its own message.

The impact of social media on education

The pace of information transfer is also changing – everything is getting faster. Users scan content quickly for a quick result (Carr, 2011). This pace of information ‘consumption’ is not driven by the content itself, but by the medium – the technology or page/app. It also affects students’ ability to accept or reject information and to critically evaluate it within the school. While everyday life is already dominated by the ‘Global Village’ (as described by McLuhan – ‘the integration of the nervous system into the world’ (McLuhan, 2000)), which connects people to the wider social world through social media and promotes the speed of information sharing – school is stuck with old media that cannot catch up with the speed of the new. The speed of social media also poses certain challenges that require teachers to acquire new competences and to teach their students not only the content, but also how to operate in the new media and what messages the media itself conveys. The available speed comes at a cost of the accuracy and reliability of the information provided online (Cooper, 2020), which also poses a challenge for the education system. The rapid, ‘here and now’ consumption of text provided by the internet and social media reduces the ability to critically analyse information (Carr, 2011); media not only conveys information but also shapes thought processes. In this case, education systems do not provide the necessary competences to participate in today’s complex media world, which requires the ability to select and understand not only the content of the media but also the media itself and its impact on society and the individual. Although McLuhan was positive about the idea of a ‘Global Village’, one of his students pointed out that the philosopher would be concerned about the faster-than-the-speed-of-light overcommunicating without depth and understanding (Cooper, 2020). Thus, looking at social media in education through McLuhanian lens, the school is at a crossroad – how and whether to incorporate social media, knowing the dangers McLuhan predicted, and how to teach the young person to critically evaluate the social media that have become inevitable, and the specific messages they carry, as well as the ability to shape the message independently of the content.

As mentioned earlier, social media is nowadays inevitable in academic environments: from sharing learning materials, informal and formal communication (e.g. Facebook, WhatsApp, GoogleClassroom), to delivering lessons in social media environments (e.g. Google Meets, Teams) and information-seeking or unconsciously receiving information in text, video, audio and other forms (Google, GoogleScholar, Wikipedia, Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, Youtube, Blogs, Snapchat, Pinterest, etc.). One of the key aims of using social media in education is to help students achieve their learning objectives and develop the necessary competences as effectively as possible (Hitchcock, 2013). Social media used for educational purposes are not inherently bad, and they are also in line with the positive aspects of the Global Village, but the importance of discussing ethical norms and promoting the aforementioned critical thinking of students by drawing attention to the influence of the media itself on their thought processes and interaction with their environment increases. Social media also help to sort and classify information (hashtags [#]), facilitate and speed up communication processes, change the rules of communication (the ability to reply or not), and become a space of communication and knowledge exchange that dictates very distinct rules that change the way people interact, both on social media itself and in real life (Robbins & Singer, 2014). These media are close and familiar ‘spaces’ for students (more than 90% of college students use Facebook (Harvard Institute of Politics, 2011)), and being able to engage and make good use of it could help the learning process.

In assessing the ability of schools and teachers to use media, it is worth recalling McLuhan’s observation, which was not directed at social media, but in the current context seems to refer to this – treating media other than books as a secondary (McLuhan, 1966). Although ‘secondary’ media have for a long time provided much more information that sensitizes more senses and becomes more memorable. This exclusion of other media reflects the backwardness of schools and their inability to respond to the needs and lives of people today (Klibavičius, 2013). McLuhan stressed the need for a deeper and more attentive reflection and analysis of media cultures – what we might now call media literacy. This highlights the need to use ‘cool’ media when working with students to promote their engagement and critical thinking, which could be helped by social media that also allows the creation of new media by commenting on the content that has already became media and so on. This encourages students’ engagement and tries to avoid passive observation by using technology that in other way would allow this – e.g. the computer. This example once again demonstrates the importance of the media message. The school is powerless to withstand the invasion of media (Marchand, 1989), so reflection is a necessity. In particular, the speed of social media, which intensively stimulates the different senses, provides instant feedback and becomes a space for aural, textual, and visual communication. This virtual learning environment encourages a shift from linear thinking to simultaneous perception (Klibavičius, 2013) – which means that media change our thinking structures.

“Extensions of man” and social media

However, by changing the structures of thinking, social media in education also embodies another of McLuhan’s ideas – media as an extension of man (1964). This author saw language itself, as a medium, as an extension of man, through which “man distances himself from wider reality”. Drawing on Bergson’s ideas, he argued that “language weakens man’s collective consciousness or intuitive perception”, but accelerates the processes of sociality, of the transmission of information, dramatically engaging all the senses, but distracting man from the bliss of the collective unconscious (1964). Although the discussion is about language, the same idea can be applied to social media, which are even more complex and create a new metalanguage in which different linguistic expressions interact, becoming a kind of continuation of the human being. How does this potentially influence interpersonal relations? How it affects the teacher-student relationship, when this new medium (e.g. Google) has more content, and its messages and information transfer processes are more productive (though not assuredly accurate)? And if language itself distances people from the collective consciousness, what is the impact of social media? What is the role of the teacher in this media? And while the main purpose of language as an extension of the human being is to find a compromise and to be social, the abyss that is being created can increase with each more complex step of the media.

Comparing social media to texts, social media seem to solve the problem of texts (to be defended by other texts, and those by others, etc.), as they can provide a sense of live conversation (e.g., Messenger, WhatsApp, Facebook), but the mere fact that it is a separate space that combines together image, sound and text, and the ability to share information, shows the features of separateness and independence – a distinct meta-level of sociality (Klibavičius, 2013). Social media such as Twitter, Youtube, Facebook seem to recreate a sense of tribe, habits of communication, Tinder, Facebook and Instagram act as chronicles, collect memories, and create online communities. But all this seems to take place in a different “space”, where the rules are dictated by the medium itself. It has already been mentioned that a large part of students’ lives also take place on social media, where images are not only being embellished, but also new lives or images are being created. Without all this being incorporated into school life, schools remain a ‘secondary media’, disconnected and distant from the other ‘real’ online social media life. The apparent creation of an educational community through social media can also be seen in the Covid-19 period when all education moved to social media. However, this did not create a more fully effective way of learning, but rather the opposite, creating an even greater emotional distance between those involved in the learning process. Social media and technology have become an extension of language, another medium, rather than an extension of a human being, thus adding another step away from the collective consciousness. Observing such an expression, we can also see the sequence created by language, which distances life and meanings from the human being as an entity – this makes the exchange of information even faster, but the abyss between the human ‘essence’ and the information it expresses or receives only widens. In education, this brings us back to the crossroads of how not to lose touch with the pupil to help him or her assimilate information, by including social media in the process, which is an inseparable continuation of life, influencing our processes of thinking and communicating and dictating the spaces and conditions of action that are often become into a “more real life” thanks to the possibility of creating it there, as if in a new meta-level.

However, there are also those who support the first idea that social media connects rather than separates, and in the educational context, using a variety of different effects (audio, visual, tactile), it “has an increasingly intense sensory stimulation effect on the learners” (Klibavičius, 2013). For instance, Teams, Googlemeets, or Zoom simulate real socialisation and educational processes, but are not yet able to engage all senses. It is like a synthesised environment that creates a simulacrum of social interaction, but does not provide the real human contact effect that attracts attention. And while social networks can still be seen as extensions of the psyche that seem to promote collective dialogue and provide access to mass information sources, they complicate and distort the understanding of each other and the rules of live communication (Klibavičius, 2013), and further distance them from the Bergsonian state of “non-speechlessness” that brings harmony and peace (McLuhan, 1964).

Possibilities

Looking at the future of social media in education through McLuhan’s eyes, we can discuss the expanding meaning of the concept of social media. Observing the tendencies in the world, we can speculate about the move of education into meta-worlds. At the same time, however, the question should be asked: what is the point? And what could this process bring to education that it does not already have? What would these social media take from those that already exist and what message and information filter would it provide? It is also possible to move completely to online teaching, but the examples we have had during the Covid period have shown that the weight of the message of social media and technology itself (the relationship between the two should be the subject of a separate essay) creates the abyss between student and teacher that has already been mentioned, changes the relationship and we have not yet learned how to live with this change. The question of what to do with the inevitability of social media still exists. Although there are many advantages to social media: it allows fast and efficient sharing of materials, reporting, receiving, finding large amounts of information from the comfort of one’s own home, teaching and learning from anywhere in the world while still keeping in touch. However, it cannot be denied that communication, and perhaps the need of its forms, will change over time and that this can and already had been heavily influenced by media, especially social media, which are changing the spaces of communication (media) and the way we perceive and process the self, the other, and the communication and sharing of information (education) processes. And although we are already talking about AI teaching (which can also be partly attributed to social media) I believe that it is the presence of media being not directly the continuum of the human being, but the continuum of another medium or several “traditional” media creates the aforementioned “abyss” of communication between human beings. And it is precisely the lack of connection that technology and media still cannot fully grasp, that is preventing a complete shift towards teaching and communication only in social media or in meta worlds.

Conclusions

Social media is an integral part of the functioning and socialization of society, not only containing the content but also actively participating in change with its messages that shape the change in our minds. Social media has become our everyday life tool and the learner’s environment in which he/she wants to operate, making the old educational practices rejectable and incomprehensible (McLuhan, 1969). However, the specificity of social media, the exclusion of social media in school, as well as the passive or negative attitudes towards the incorporation of these media in everyday life, create a void in the teaching relationship. Teachers’ synthetic engagement with social media also often creates alienation and maintains a ‘rear-view mirror’ situation, as the teaching system is not run by the students themselves. And while social media are their own “community” of individuals that allows interactive and alleged participation in (or rather secret observation of) the lives of others, their use in the education system needs to be well thought out and evaluated, by discussing it with the users themselves and by changing the role of the teacher into a facilitator – who points the direction and teaches to observe the consequences and the impact, rather than explaining the reality that is currently available (thanks to the advent of the written word and the Internet) in the same medium in which the social media exist. Technological advances reveal the versatility, multifunctionality, and complexity of new media – for example, a smartphone combines the functions of a call, a web browser, email, a music player, and a photo or video camera (Klibavičius, 2013). Due to the influence of media, today’s students (‘digital natives’) see and understand their environment differently, solve and understand problems differently, and therefore expect a similar environment (social media) in the classroom. In today’s school, it is important not only to provide the knowledge but also to teach how to act in the media, how to search and select information, ethical issues, boundary making, communication, critical thinking, observing not only the content of the media but also the messages they produce.

References

1. Baudrillard, J., 1981. Simuliakrai ir simuliacija.

2. Carr, N., 2011. Is Google making us stupid? In M. Bauerlein (Ed.), The digital divide. New York, NY: Peter Group, Inc

3. Cooper, T., 2020. McLuhan, Social Media and Ethics, New Explorations. Studies in Culture and Communication. Vol 1, No 2. Available at: [cignatov,+03_Cooper_MediaEthics.pdf]

4. Harvard Institute on Politics, 2011. IOP youth polling: Spring 2011 survey. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Kennedy School of Government

5. Hitchcock, L. I., 2013. Twitter learning activities for social work competencies. Teaching Social Work. Available at: [http://laureliversonhitchcock.org/2013/12/18/twitter-learning-activities-for-social-workcompetencies/]

6. Klibavičius, D., 2013. Naujosios medijos kaip klasikinės ugdymo paradigmos alternatyva, Problemos 2013. Available at: [827-Article Text-398-1-10-20181109.pdf]

7. Levinson, P., 2001. Digital McLuhan. New York, NY: Routledge. Lieberman, B. (1967). The greatest defect of McLuhan’s theory is the complete rejection 93 of any role for the content of communication. In G. Stearn (Ed.)

8. Marchand, P., 1989. Marshall McLuhan: the medium and the messenger. New York: Ticknor & Fields.

9. McLuhan, M., 1964. Kaip suprasti medijas. Žmogaus tęsiniai. Available at: [McLuhan_Marshall_Kaip_suprasti_medijas_Zmogaus_tesiniai_2003_LT.pdf]

10. McLuhan, M., 1966. The effect of the printed book on language in the 16th century. In: E. Carpenter and M. McLuhan, ed. Explorations in Communication: an anthology. Boston: Beacon Press, p. 125–135.

11. McLuhan, M., 1969. The Playboy Interview: Marshall McLuhan – A Candid Conversation with the High Priest of Popcult and Metaphysician of Media. Playboy Magazine (March).

12. McLuhan, M., 2000. Foresees the Global Village. Available at: [http://www.livinginternet.com/ i/ii_mcluhan.htm]

13. Oxford English Dictionary (2013) Social media. Available at: [http://oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/social-media?q=social media]

14. Robbins, S., P., Singer, J., B., 2014. From the Editor—The Medium Is the Message: Integrating Social Media and Social Work Education, Journal of Social Work Education, 50:3, 387-390. Available at: [From the Editor The Medium Is the Message Integrating Social Media and Social Work Education.pdf]

Background

Over the past few months, the outbreak of the coronavirus (‘COVID-19 crisis’) has risen to the scale of a global pandemic. A total of 213 countries, areas or territories are currently affected. As more and more countries implement a range of measures to contain the COVID-19 crisis, including travel restrictions and various forms of ‘lockdown’, the effects of the crisis can be seen in almost all areas of society.

The world of education has been no exception. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced a digitalisation of education and rapidly pushed education and training systems to explore new ways of teaching and learning. Stakeholders at all levels – governments, public and private organisations, communities and individuals – have been developing and implementing innovations and creative solutions to ensure that education systems can continue functioning in light of this. The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on adult learning (AL) has also been acute. Participation in adult learning has been impacted, with adult learning providers and educators facing multiple challenges in continuing their learning offers and adapting to the situation. The crisis, and its widespread impact on economies and societies globally, has also highlighted the prominent role for adult learning in a COVID-19 affected world. Within and beyond the crisis, adult learning is key in ensuring people can obtain the (new) skills and competences required in a COVID-affected labour market and society.

Aim of the report

This report aims to provide an insight into the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on adult learning, as well as into the role adult learning can play in the context of the crisis (and future similar crises).

These insights aim to inform the discussion at Member State and European level on adult learning.The report focuses on the following guiding questions:

- What are the short- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on areas that are indirectly affecting adult learning systems (e.g. economy, labour market etc.)?

- What are the short- and long-term impacts on adult learning systems (impact on providers and their teaching/training staff, modes of delivery)?

- What are the short- and long-term impacts on adult learners (as worker, parent, teacher and learner)?

- How is the adult learning system responding to the situation and to the learning needs of adults in particular?

- What are the short- and long-term needs of adult learning systems so that they can provide services that better respond to the current situation?

- What needs to be considered most urgently for adult learning systems to be able to contribute to the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis?

These questions are supported by the following sub-questions:

- How (well) is the sudden transition to distant learning going for adult learning providers and adult learners. Are there differences in how types of providers make the transition (how easy/difficult is it for small education providers, for example)?

- What are (good) examples of initiatives emerging from the adult learning sector?

- Are there particular programmes, curricula, subject fields, etc. that are in higher demand currently?

- What stands out as the main benefit(s) that adult learning can offer people in coping with lockdown, confinement and all the other changes brought on by COVID-19? Why is adult learning now more important than ever?

- What are possible “impact scenarios” to consider in terms of what the world will look like ‘after’ the COVID-19 crisis – and what would this mean for adult learning?

- Does this crisis offer the adult learning sector a chance to show its worth and to emerge as an important sector?

The focus of this report is the whole adult learning system or environment. The report does not differentiate between sub-sectors focusing on basic skills, vocational education and training and in-company training, liberal education or adult learning in higher education. This is done to emphasise the sector-wide approach needed to respond to the emerging challenges and to emphasise that all sub-sectors have their own valuable contribution to the whole sector.

In literature and discussion papers on the COVID-19 crisis, other terms are used, such as ‘postCOVID-19 situation’, or ‘the new normal’. We do not yet know the long-term impact of COVID-19 on our future societies. This depends on many variables, such as whether there will be a second (or third) wave of infections, whether a vaccine will be found and widely available, whether the current situation leads to other challenges and tensions globally, or even whether another Corona-type virus will emerge. What we do, however, know is that societies and individuals need to prepare to cope with a new situation of insecurity, and the potential emergence of sudden shocks and unexpected circumstances, in the future, as experienced in the context of COVID-19. In this report, we use the term ‘COVID-19 affected future’ to refer to this situation. This term refers to the longer-term implications of COVID-19 – approximately one or two years from the outbreak – and refers to a world that is both potentially affected by pandemics, as well as facing increased health and environmental threats.

Full report (*.pdf)

Objective of the report

Society and the world of work are changing at a fast pace. Digitalisation, transition to a carbon free economy, population ageing, and globalisation have a deep impact on the way we live, learn and work and on the skills we need to do so.

Against the background of stagnating participation rates in adult learning, the aim of this report is to analyse and explore policy options for fit-for-purpose adult learning systems and their governance that support all individuals in their continuing upskilling and reskilling. While policy measures can target various actors in a skills ecosystem (employers, education and training providers, individuals themselves), the focus in this report is on policies for empowering individuals to undertake up-/re-skilling in a broad sense (basic skills/key competences, vocational skills and active citizenship development). This is also consistent with the right to quality and inclusive education, training and lifelong learning set under the European Pillar of Social Rights.

For the purpose of this report, adult learning is defined, in accordance with the European Agenda for Adult Learning, as ‘all forms of learning undertaken by adults after having left initial education and training’, however far this process may have gone (e.g. including tertiary education). Thus it can include learning activities as varied as undertaking a new professional qualification with a view to radically changing career direction, joining an evening language or art course, training to gain a first qualification or developing digital skills in a local library.

This report is drafted by the ET2020 Working Group on Adult Learning (WGAL), which has representatives from Member States, Candidate Countries, social partners and European Agencies (Cedefop, European Training Foundation (ETF), Eurydice). The Working Group is supported by the European Commission, DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

This report is drafted on the basis of information gathered from the countries during the period of 2018-2019; publications presented and discussed within the WGAL; policies analysed during a Peer Learning Activity (PLA) and input of the WGAL members.

Empowerment and adult learning

While employers and education and training providers can be incentivised to create the right conditions for accessing various learning trajectories, it is equally vital that individuals themselves have the motivation and the means to engage in learning. This is why empowerment can play an important role in shaping successful adult learning policies. In line with Oscar Freire, empowerment can be an objective of learning, and the result of adult learning activities and policies should be a more empowered individual and society; whereas according to Malcolm Knowles, empowering is a key characteristic of the learner.

Either way, empowerment is intrinsically connected to adult learning, both as a means (condition) and as the aim (objective) of learning. Therefore, adult learning policies will have to be able to both support the development of empowerment, as well as build upon it to solve dispositional, situational and institutional barriers for learning. Thus, empowerment plays a role in all adult learning related activities, or, in other words, in the entire adult learning pathway – from first (re-) encounter with learning, to becoming a lifelong learner.

Policy pointers for systems and governance that empower adults to up-/re-skill

A holistic and fit-for-purpose adult learning system that empowers adults to reskill and upskill includes the following:

Policy pointer 1. Individualised approaches and outreach to specific groups: A strong adult learning system reaches out to specific target groups by going to where these adults are and works with community ambassadors and/or different institutions and organisations active at local level.

Furthermore, such individualised approaches and outreach make information on guidance services, training and (job) opportunities easily accessible to all; they are tailored to the needs and potential of the adult as a whole person (combining employability and wider personal development goals as well as addressing possible social and health issues) and enables the adult to take ownership of the individualised guidance and training pathway.

Policy pointer 2. Partnership approaches in which roles and responsibilities are clearly defined and monitored: A strong adult learning system that supports adults to be empowered for reskilling and upskilling includes is based on an operational partnership between all relevant stakeholders (education and training sector, labour market sector, cultural sector and other relevant institutions and organizations, in areas such as leisure, civil society, family and social welfare, health, government, including local government), at the most appropriate level. In the partnerships roles and responsibilities should be clearly defined and agreed upon. Finally, the partnerships need to be monitored and evaluated.

Policy pointer 3. Policy frameworks that cover different policy areas; include coordination and a stimulating financial mechanism: A strong adult learning system that supports adults to be empowered for reskilling and upskilling includes a policy framework that is based on a coherent and overarching approach in which different policy fields (education, adult learning, culture, civic engagement, family and social welfare, entrepreneurship and employment, life wide guidance) are effectively included; that is based on a strong coordination mechanism (or coordinator); that is sufficiently resourced; and includes the right (financial) incentives targeted both at adults and institutions.

Policy pointer 4. Quality assurance mechanism of learning provision, guidance services and outreach activities: A strong adult learning system that supports adults to be empowered for reskilling and upskilling includes an approach that is based on a quality assurance approach that ensures a high quality level of guidance and training services (that includes external audits); use of monitoring and evaluation information to improve services; and finally research on effective guidance approaches and (regional/future) skills needs.

Policy pointer 5. Guidance staff development and their training approaches: A strong adult learning system that supports adults to be empowered for reskilling and upskilling includes an approach to guidance staff development that ensures that the staff has the right competences, skills and qualifications and is able to continuously development in the profession through upskilling courses, mentoring, supervision and learning while working.

Full version of the report (*.pdf)

The learning resources in SEDETT are structured to consist of a set of three learning modules that each have a written module text and an example of a training workshop that has been drawn from the module text. The three modules are:

- Social enterprise, its concepts, forms and governance (Module 1, *.pdf)

- Leadership, human resources and operational management in social enterprise (Module 2, *.pdf)

- Finance, revenue generation, networking and capacity assessment (Module 3, *.pdf)

The written text for each module is structured to provide an index listing each sub-unit of material within the module, the module aims and the approach taken to generate the material.

The core written material in the module texts reflect the real life experiences of the social enterprise actors interviewed from the case study organisations that contributed to the SEDETT project.

The core written material in each of the module texts can be used by educators and trainers to shape and form learning experiences that are appropriate to the level of learner and the type of course to be provided.

Also there are files that contain background descriptive information about the project case study organisations, social enterprise definitions, business models in-use and some country specific information on the governance of social enterprises.

SEDETT educational resources was developed within framework of Erasmus+ project “Social Enterprise Development, Education and Training Tools (SEDETT)”.

The proposed project is innovative in the terms set out by the European Commission (http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-10-473_fr.htm) in that in less well developed countries in Europe, such as Lithuania, Romania and Poland it will help to speed up and improve the way social enterprises are conceived by (i) developing a broader understanding of the purposes of social enterprise, in terms of their mission, ethics, governance, leadership and management structures and impact assessments; and in so doing this work will assist in developing a culture of S.E. in those parts of Europe where such approaches are not yet fully embedded. The need for such work to build capacity has been highlighted in the work of the OECD/EMES research network generally and in particular by Young and Lecy (2014) who indicate that in Europe there is not one single definition of social enterprise but rather a continuum that spans from pure profit seeking organisations to organisations focused to social impact. As a result they call for more evidence based research from case studies to be done that aids the definition of the boundaries between S.E. with commercial and social missions in terms of their legal context, governance, leadership and management approaches, stakeholder involvement, risk and financial management strategies and value impact measurement practices. In addition, Spear and Bidet’s (2005) wide ranging analysis of social enterprise across twelve European countries found that it was a rapidly emerging trend that was helping to address the social exclusion in labour markets. This work called for more research into the issues affecting the sustainability and growth of social enterprises and called in particular for empirical work to be done that identifies typologies of social enterprise organisations and the development of models of good practice so as to enable the sector to thrive in all parts of Europe.

More about the project: www.sedett.eu

Statnickė G. (2016). Managing generational diversity in the organization. Global Academic Society Journal: Social Science Insight, Vol. 8, No. 18, pp. 9-19. ISSN 2029-0365 [www.ScholarArticles.net]

Author:

Gita Statnickė

Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania

Klaipėda State University of Applied Sciences, Lithuania

Abstract

In the era of constant changes, innovations and business transformations, the competitive pressure forces organizations to look for and invest in staff, which acquires necessary knowledge, skills and ideas. The Generation Y is entering and gradually taking stronger positions in the labour market. The Generation Y differs considerably from the Baby Boom Generation (1943-1960) and the Generation X (1961-1981) not only in terms of the dominant personal traits and values, but also in terms of the essential approach to work. Generational diversity management is becoming one of the most important parts of the human resources management process. On the basis of the Theory of Generations, this article attempts to provide the conception of generational diversity identifying the main characteristics of generations dominant in the labour market, and to discuss the theoretical aspects of generational diversity management in an organization.

Introduction

Today’s market transformation, fostered by the restructured economy, Internet and technological progress, globalisation, demographic problems, constantly growing and changing consumer needs, encourages business organizations to rethink staff management strategies and methods. Business representatives and scholars unanimously agree that the era of uncertainty, constant changes, innovations and business transformation has begun. The research report “Global Talent 2021” emphasises that advanced technologies (42%), globalisation (41%), demography (38%), customer needs (38%) and competition (38%) are the main factors that will have the major impact on the organization’s strategic staff management in the nearest decade. Competitive pressure forces organizations to look for and invest in staff, which acquires necessary knowledge, skills and ideas. Staff members, who belong to different generations, have different capacities to adapt to the changes (Mathis & Jackson, 2012) and are unique in their abilities, competence and experience. Although generational diversity management is becoming one of the most important parts of the human resources management process, there is still a lack of research works, which could not only help to accurately identify generations and determine their essential differences in the labour market, but also would provide generational diversity management opportunities in an organization.

The object of the research is generational diversity management in an organization.

The aim of the research is to analyse the theoretical aspects of generational diversity management based on the Theory of Generations.

Objectives:

1. To provide the conception of generational diversity identifying the main characteristics of generations dominant in the labour market;

2. To discuss the theoretical aspects of generational diversity management in an organization.

The following research data collection method has been applied: scientific literature analysis.

Generational Diversity Conception

Many sciences, such as sociology, philosophy, educational sciences, etc., deal with the concept of generational diversity. The Dictionary of Contemporary Lithuanian (Lith. Dabartinės lietuvių kalbos žodynas) (2012) defines generation as “people of similar age living at the same period of time”. In the social sciences, generation is understood as a group of people, born, matured and living in the same historical period: Mannheim (1952) describes generation as a group of people of the same age, united by a certain memorable historical event. According to Bourdieu (1993), generation is a culturally conditioned phenomenon, i.e. different generations typically have certain interests, beliefs and tendencies, meanwhile, inside the generation, a struggle is taking place in time regarding cultural and economic resources. As assumed by Mead (1970), a generational conflict arises in the world, because a younger generation rebels against the older generation, which manages the social control mechanisms, and therefore, according to Buckingham & Willett (2006), it is important to evaluate the role of new technologies, media and consumption habits when determining the boundaries of generations. The boundaries of generations “crystallise” in the course of reverse socialisation, when children “force” their parents to adapt to new and changing socio-technological conditions. Thus, a “generational order” is not imposed on an individual passively, but is rather a dynamic process that requires personal engagement of the individual (Labanauskas, 2008, pp. 64-75).

In the scientific literature, an individual is usually assigned to a certain generation by the date of birth. It is assumed, that one generation covers a period of 20 years. Here, however, one of the main problems arises – due to insufficient systemic research on generations in different European and other counties, there is a lack of a uniform categorization into generations. According to Stanišauskienė (2015), the Theory of Generations is mainly developed by sociologists (McCrindle in 2014; Comeau & Tung in 2014; Martin & Martins in 2012), although the generational differences are also analysed by other scholars of social sciences. Educationists emphasise the educational peculiarities of the new Generation Z (Pečiuliauskienė et al., 2013) as well as the learning features of the Generation Y (Wilson & Gerber, 2008). In the field of management, discussions are held about the new generation of leaders and their styles of management (Hershaterr & Epstein, 2010; Ng et al., 2012). The psychologists of organizations talk about the Generation Y that is entering and gradually taking stronger positions in the labour market (Flagler & Thompson, 2014). The representatives of the Generation Y, which is entering the labour market, feature different values and behaviour in comparison to the Generation X, which is still dominant in the labour market (Howe & Strauss, 1991). After a decade or more, when the Generation Y becomes dominant in the labour world, the values and behaviour typical to this generation will form the working style and values of organizations (2015, pp. 1-2).

Generations are categorized according to the time of birth not only by the pioneers of the Theory of Generations, such as Howe & Strauss (1991), but also by such scholars as Martin & Tulgan (2001), Raines (2003), Eisner (2005), Twenge (2006), etc. Although, the most frequently applied Theory of Generations in practice is The Strauss-Howe Generational Theory, if compared to the categorization of generations suggested by other scholars, the beginning and / or end periods of the assignment to certain generations do not always match, and there are also cases when some periods overlap. For example, Howe & Strauss (1991) distinguish the following generations in the Theory of Generations: the Lost Generation (born in 1883-1900), the Greatest Generation (born in 1901-1924), the Silent (Traditional) Generation (born in 1925-1942), the Baby Boom Generation (born in 1943-1960), the Generation X (born in 1961-1981), the Y / Millennial Generation (born in 1982-2004), the Z / Homeland Generation (born in 2005 and later). McCrindle & Wolfinger (2010) provide the following categorization of generations: the Great Depression Generation (born in 1912-1921); the World War II Generation (born in 1922-1927); the Post-War Generation (born in 1928-1945); the Baby Boom Generation (born in 1946-1954); the Baby Boom Generation II (born in 1955-1965); the Generation X (born 1966-1976); the Generation Y (born in 1977-1994); and the Generation Z (born in 1995-2012). According to The Sloan Center on Aging & Work (2011), managing the generational diversity in an organization, attention is focused on the following main generations: the Veterans (born before 1946 and currently over 65-70 years old); the Baby Boomers (born in 1946-1964); the Generation X (born in 1965-1980); and the Generation Y (born in 1981-2000).

So, currently, there are 5 generations that live and interact together: the Silent Generation has practically abandoned the labour market, the number of representatives of the Baby Boom Generation is decreasing, the Generation X is dominant, the Generation Y is strengthening its positions in the labour market, and the representatives of the Generation Z are already entering the labour market.

If the issue of categorization to different generations is still under discussions, in any case, it has been agreed that the changes in the society bring changes to the system of values, new generations are occurring, and each generation is distinguished by the dominant personal traits, values and approach to work (Table 1).

{insert Table 1 here}

The Generation Y is entering and gradually taking stronger positions in the labour market. The Generation Y differs considerably from the Baby Boom Generation (1943-1960) and the Generation X (1961-1981) not only in terms of the dominant personal traits and values, but also in terms of the essential approach to work. As Table 1 shows, the Baby Boom Generation values work as a meaningful part of their lives, and the representatives of the Generation X pursue to be evaluated; meanwhile, the Generation Y agree to work hard only if their work is meaningful. The Silent Generation and the Baby Boom Generation are loyal to the organization; the Generation X, although generally disloyal, prefer stability, value each work position as a certain stage of their career; meanwhile, loyalty to one organization of the Generation Y declines because they pursue continuous changes. The Silent Generation is first and foremost motivated by financial reward, and only then by cooperation and employer’s evaluation; meanwhile, the Generation Z is firstly motivated by the acquisition of innovative market and technical knowledge, mobility opportunities, and only then by financial reward. The process itself and teamwork are of importance to the Silent Generation, meanwhile the Generation X appreciate quality and personal freedom, prefer flexible working hours and style, like to lead, and achieve very good results only if they are appreciated; the representatives of the Generation Y like to create, dislike hierarchy, pursue independent and non-binding working environment; and the Generation Z is characterised by a lack of attention, multitasking, creativity, disregard of authorities, technological ingenuity, and tolerance.

Theoretical Aspects of Generational Diversity Management in the Organization

In scientific literature, the term diversity management is most often associated with such characteristic features as gender, race, ethnicity, health condition (e.g. disability), etc., meanwhile categorization to a certain generation is neither separately distinguished nor emphasised. Kuprytė & Salatkienė (2011) assume that diversity management is active and conscious development of future, oriented on the value-based company’s strategy; a managerial process, where differences and similarities of people are used as a potential in an organization; a process, which creates added value to the company. Čiutienė & Railaitė (2013) point out that, according to Rosado (2006), generational diversity management should be understood here as “a comprehensive holistic process, which aims at managing the differences which are brought by people, in order to ensure productive interaction of all of them in a company”; diversity management comprises two main dimensions: the core, including human’s age, gender, race, sexual orientation, disability, etc., and the psycho-social spiritual dimension, which is usually externally invisible and covers the human’s value system, worldview, thinking, etc. These differences may lead to conflict situations among people with certain different characteristics; however, effective management of such differences may become a great advantage.

The Generation Y is entering and gradually taking stronger positions in the labour market. The Generation Y differs considerably from the Baby Boom Generation (1943-1960) and the Generation X (1961-1981) not only in terms of the dominant personal traits and values, but also in terms of the essential approach to work. As Table 1 shows, the Baby Boom Generation values work as a meaningful part of their lives, and the representatives of the Generation X pursue to be evaluated; meanwhile, the Generation Y agree to work hard only if their work is meaningful. The Silent Generation and the Baby Boom Generation are loyal to the organization; the Generation X, although generally disloyal, prefer stability, value each work position as a certain stage of their career; meanwhile, loyalty to one organization of the Generation Y declines because they pursue continuous changes. The Silent Generation is first and foremost motivated by financial reward, and only then by cooperation and employer’s evaluation; meanwhile, the Generation Z is firstly motivated by the acquisition of innovative market and technical knowledge, mobility opportunities, and only then by financial reward. The process itself and teamwork are of importance to the Silent Generation, meanwhile the Generation X appreciate quality and personal freedom, prefer flexible working hours and style, like to lead, and achieve very good results only if they are appreciated; the representatives of the Generation Y like to create, dislike hierarchy, pursue independent and non-binding working environment; and the Generation Z is characterised by a lack of attention, multitasking, creativity, disregard of authorities, technological ingenuity, and tolerance.

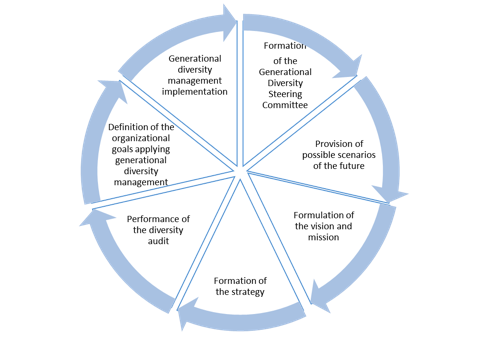

Figure 1. The Generational Diversity Management Implementation Process

Source: according to Keil et al. (2007)

In order to assess the opportunities of generational diversity management in an organization, first and foremost, according to Murphy (2007), it is recommended to carry out research in order to determine the generations and their proportions in the target organization.

The Training Manual for Diversity Management emphasises the diversity management implementation process. This process is provided in Figure 1 and is often understood as the organizational learning process that involves the formation of the Generational Diversity Steering Committee in the organization; provision of possible scenarios of the future for the forthcoming 10-20 years, focusing on the generational diversity; based on the scenario selected previously, formulation of the vision and mission and formation of the strategy, with the emphasis on how the idea of diversity management will be implemented; performance of the diversity audit in order to assess the situation in the organization; definition of the organizational goals applying diversity management; and the very diversity management implementation (adapted according to Keil et al., 2007).

Generational diversity management in the organization is a recommended methodological tactics in order to solve the problem of older people employment, because a team of employees, formed with respect to generational diversity and differences, can deal with the tasks assigned to them more effectively, because a team formed on the basis of this principle disposes more extensive information, experience and skills to make decisions, and therefore, the outcomes of their performance tend to be much better. Based on the data of Dublin Foundation study, successful organization management, focused on the staff of different generations, is determined by the following factors: attention to the age-related problems, the overall national policy regarding support to this type management, caution in the stages of its creation and implementation, cooperation of all the stakeholders taking into consideration this aspect, evaluation and calculation of costs and benefits. Petrulis (2015, p. 56) quotes Bombiak (2014, pp. 113-114), who specifies that organization leaders have to understand that managing people that belong to different generations is the element of diversity management based on different measures, which facilitate the working conditions of older people and increase their work efficiency. Čiutienė & Railaitė (2013) suggest that only if the current situation is assessed and the peculiarities of managing different generations are analysed, it is possible to provide the following main generational diversity management measures: creation of a suitable working environment, effective communication and conflict resolution, staff training organization, knowledge transfer assurance, creation of flexible working conditions, and promotion of healthcare programmes.

Conclusions

The categorization to different generations is still under discussion, however, in any case it is agreed that each generation is distinguished by the dominant personal traits, values and approach to work. The Generation Y is entering and gradually taking stronger positions in the labour market. The Generation Y differs considerably from the Baby Boom Generation (1943-1960) and the Generation X (1961-1981) not only in terms of the dominant personal traits and values, but also in terms of the essential approach to work. After a decade or more, when the Generation Y becomes dominant in the labour world, the values and behaviour typical to this generation will form the working style and values of organizations. The Baby Boom Generation value work as a meaningful part of their life, and the Generation X pursue to be evaluated, meanwhile, the Generation Y agree to work hard only if their work is meaningful. If the Silent Generation and the Baby Boom Generation are loyal to the organization; the Generation Y pursue continuous changes. The process itself and teamwork are of importance to the Silent Generation, meanwhile the Generation X appreciate quality and personal freedom, prefer flexible working hours and style, like to lead, and achieve very good results only if they are appreciated; the representatives of the Generation Y like to create, dislike hierarchy, pursue independent and non-binding working environment; and the Generation Z is characterised by a lack of attention, multitasking, creativity, disregard of authorities, technological ingenuity, and tolerance.

A team formed taking into consideration the generational diversity dispose more extensive information, experience and skills to make decisions, and therefore, the outcomes of the performance tend to be much better. The diversity management implementation process, as emphasised in the scientific literature, includes the formation of the Generational Diversity Steering Committee, provision of possible scenarios of the future, formation of the vision, mission and strategy, performance of the generational diversity audit, definition of the organizational goals applying diversity management, as well as the very diversity management implementation. Effective generational diversity management, capable of becoming a great competitive advantage of an organization, is only possible upon the creation of flexible working conditions and suitable working environment, effective communication and conflict resolution, organisation of trainings that meet the needs of the staff, assurance of the knowledge transfer system, as well as application of other necessary measures.

References

1. Bourdieu, P. (1993). Sociology in Question. Sage Publications.

2. Buckingham, D., Willett, R. (2006). Digital Generations – Children, Young People, and the New Media. New York: Routledge.

3. Čiutienė, R., Railaitė, R. (2013). Darbuotojų amžiaus įvairovės valdymas (= Employees Age Diversity Management). Organizacijų vadyba: sisteminiai tyrimai (= Management of Organizations: Systemic Research), vol. 68, pp. 27-40. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University Press.

4. Dictionary of Contemporary Lithuanian (= Dabartinės lietuvių kalbos žodynas) (2012). Vilnius: Institute of the Lithuanian Language.

5. Eisner, S. P. (2005). Managing Generation Y. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 70(4), pp. 4-15.

6. Flagler, W., Thompson, T. (2014). 21st Century Skills: Bridging the Four Generations in Today’s Workforce. Internet access: http://cannexus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/21st-Century-Skills-Bridhing-the-FourGenerations-in-Todays-Workforce-Flager-Thompson.pdf, viewed on 29/04/2016.

7. Hershaterr, A., Epstein, M. (2010). Millennials and the World of Work: Organization and Management Perspective. Journal of Business and Psychology 25, pp. 211-223.

8. Howe, N., Strauss, W. (1991). Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. Perennial: an Imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

9. Keil, M., Amershi, B., Holmes, S., Jablonski, H., Lüthi, E., Matoba, K., Plett, A., Unruh, K. (2007). Training Manual for Diversity Management. Antidiscrimination and Diversity Training, VT/2006/009, pp. 14-16.

10. Kuprytė, J., Salatkienė, A. (2011). Įvairovė įmonėse: kaip pritraukti ir išlaikyti skirtingus darbuotojus (= Diversity in Companies: How to Attract and Retain Different Employees). Vilnius: Public Enterprise “SOPA”.

11. Labanauskas, L. (2008). Profesinės karjeros ir migracijos sąryšis: kartos studija (= The Relationship between Career and Migration: a Study of Generation). Filosofija. Sociologija (= Philosophy. Sociology). Vol. 19. No. 2, pp. 64-75.

12. Mannheim, K. (1952). The Problem of Generations, in Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge by Karl Mannheim, ed. P. Kecskemeti. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

13. Martin, C.A., Tulgan, B., (2001). Managing Generation Y: Global Citizens Born in the Late Seventies and Early Eighties. Human Resource Development. HRD Press. Amherst, Massachusetts.

14. Mathis, R. L., Jackson, J. H. (2012). Human Resource Management – Essential Perspectives, 6th Edition. Mason: Cengage Learning.

15. McCrindle, M. (2014). The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generation. 3rd edition. McCrindle Researche Pty Ltd, Australia. Internet access: http://mccrindle.com.au/resources/The-ABC-of-XYZ_Chapter-1.pdf, viewed on 01/05/2016.

16. McCrindle, M., Wolfinger, E. (2010). The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generation. Australia: University of New South Wales Press Ltd.

17. Mead, M. (1970). Culture and Commitment: the Study of a Generation Gap. Garden City: Natural History Press.

18. Murphy, S. A. (2007). Leading a Multigenerational Workforce. AARP. Washington.

19. Narijauskaitė, I., Stonytė, M. (2011). Kartų skirtumai darbo rinkoje: požiūris į darbą (= Generational Differences in the Labour Market: Approach to Work). Tiltas į ateitį (= The Bridge to the Future). Kaunas: Technologija (= Technology) 2012, No. 1 (5). pp. 133-137.

20. Ng, E., Lyons, S.T., Schweitzer, L., (2012). Managing the new workforce: International perspectives on the millennial generation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

21. Pečiuliauskienė, P., Valantinaitė, I., Malonaitienė, V. (2013). Z karta: kūrybingumas ir integracija (= Generation Z: Creativity and Integration. Vilnius: Edukologija (=Education).

22. Petrulis, A. (2015). Vadovavimas darbuotojams demografinių pokyčių kontekste (= Management Employees in the Context of Demographic Changes). Regional Formation and Development Studies, vol. 16, No 2, pp. 54-65.

23. Raines, Cl. (2003). Connecting Generations: The Sourcebook for a New Workplace. Melno Park, CA: Crisp Publications.

24. Stanišauskienė, V. (2015). Karjeros sprendimus lemiančių veiksnių dinamika kartų kaitos kontekste (= The Dynamics of Factors Determining Career Decisions in the Context of Generation Change). Tiltai (=Bridges). Vol. 2, ISSN 1392-3137 (Print), ISSN 2351-6569 (Online), pp. 1-20.

25. The Sloan Center on Aging & Work. (2011). Age: 18. A 21st Century Diversity Imperative. Executive Case Report No 4.

26. Twenge, J. M. (2006). Generation Me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled and more miserable than ever before. New York, NY: Free Press.

27. Wilson, M., Gerber, L. E. (2008, Fall). How Generational Theory Can Improve Teaching: Strategies for Working with the Millennials. Currents in Teaching and Learning, 1(1), pp. 29-44.